Wires History

One of the recent additions to our portfolio of plugins is based on a little-known, but fascinating thread in the history of sound recording, a thread that dates back to the 19th century and extends through the Cold War.

We’ve collaborated with German composer and YouTuber Hainbach to create an emulation of a Soviet military wire recorder from the 1970s, modeled on the MN61 unit Hainbach owns. Wires’ history is as compelling as its sound. Wires goes above and beyond the Lo-Fi standard set by tape emulations. Wires turns the most boring signals into sepia coloured magic.

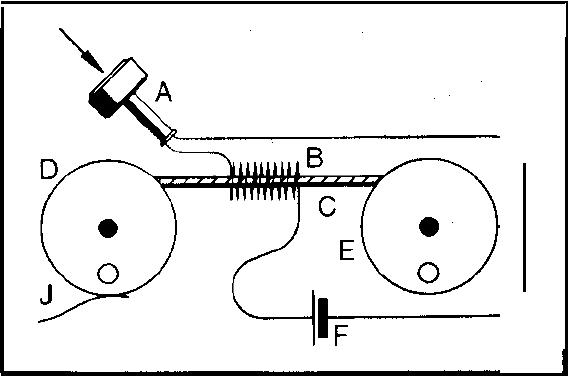

The dominance of magnetic tape in the 1950s to the 1990s overshadowed some earlier forms of recording technology. While magnetic tape all but entirely beat out steel wires, tape owes its basic idea to wire’s groundwork. Wire recording and tape recording operate on the same premise: a write head uses electric current to reorganize magnetic particles on a material’s surface as it runs across the write head. This would save it for later, when the machine would reverse the process and create current with the magnetic particles passing through the read head.

Museum of magnetic sound recording

American inventor Oberlin Smith conducted early investigations into magnetic recording in the 19th century. He hypothesized about applying magnetic particles to strips of silk, but his efforts proved overambitious and ahead of their time, and his work ended up in the form of published writings. Inspired by Oberlin’s writings, a Danish engineer named Valdemar Poulsen invented a wire recording device he referred to as the Telegraphone in 1898. The Telegraphone saw little commercial success. At the time, wax cylinders were the dominant technology used for recording and storing audio. Even so, wire had numerous advantages: the wire was extremely thin and could be stored in great lengths while taking up very little space; the length of the wire allowed for very fast playback speed; wire was easy to edit, requiring simple cuts and splices that were largely unnoticeable to the ear thanks to the fast playback speed; and wire was fire resistant. Smith himself listed some of wire’s advantages as “cheap, simple, delicacy.”

Governments and technology corporations noted wire’s preferable traits, and the wire recorder had its heyday in the middle of the 20th century, serving in myriad military and official roles all over the world as geopolitics transitioned from World War to Cold War. These include:

– During World War 2, the US Army made “Ghost Armies” composed of inflatable rubber tanks and wire-recorded battle sounds blasted through loudspeakers, with the intention of convincing enemy reconnaissance that there were large troop movements where no troops actually were. The Army deemed the operation a massive success.

– David Boder used Steel wires to record the oral histories of Holocaust survivors in 1946, thought to possibly be the first long-form oral history recordings.

– The U.S. National Bureau of Standards used wire as a storage device for one of the first memory-based computer programs in the world, the Standards Electronic Automatic Computer.

But if tape took over wire recording over the course of the 1950s, why was anyone using any wire recording devices in the 1970s?

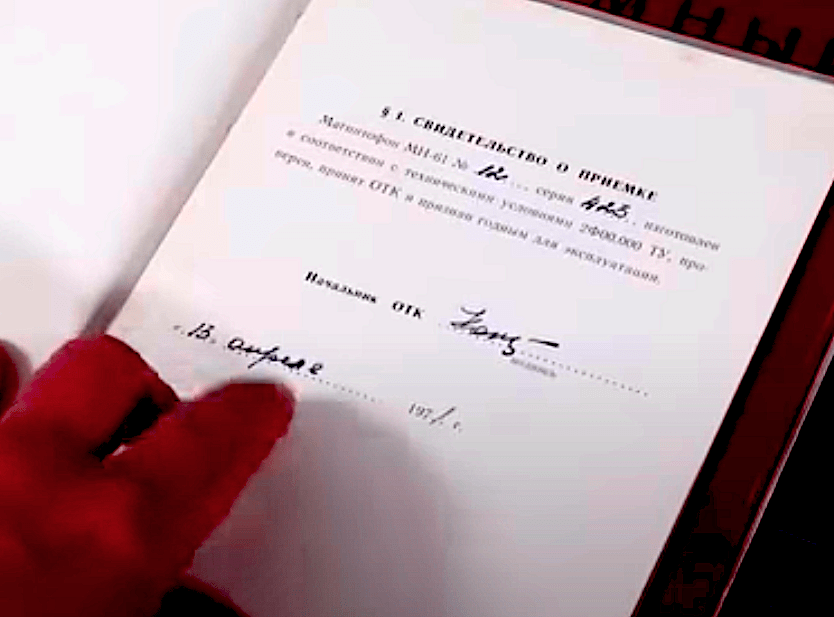

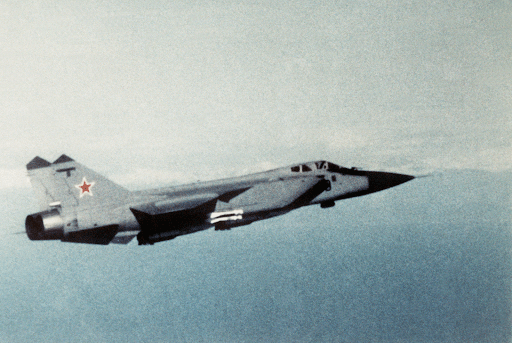

The Soviet Union manufactured the MN61 wire recorder for the security forces of the Soviet Union and its allies, producing them in Lithuania. The USSR made even more ruggedized versions of these units as black boxes, devices that record data during an airplane’s flight. As far as Hainbach can deduce, there were two main reasons for the USSR choosing wire in this role: wire is fireproof, which makes them great as black boxes, retrievable and undamaged after a plane crash, and the wire’s length increased the available recording time. While it’s peculiar that a world superpower would be the last one using a technology that was largely obsolete, the wire worked well, and so the Soviet Union produced these wire recorders from 1961 to the 1970s.

Hainbach’s bought his MN61 unit in museum condition from eBay, including the original headphones, handpiece microphone, user manual, schematics, and a certification saying that it was made in 1971. It also came with some leftover recordings of east german military operations, left on the reels sent with the unit.

While Wires is a faithful, exhaustive emulation of Hainbach’s MN61, you probably don’t run your DAW on a MiG-31 fighter jet. Therefore, we made some additions to the MN61 so that a piece of 20th-century military equipment could excel as a 21st-century plugin. These include a master dry/wet knob, soft clipping, the options to start and stop the wire, hiss, and motor noise knobs, an echo section, and much more, which allows for Wires to seamlessly integrate archaic audio technology into modern music production. You might even find some residual military recordings found on Hainbach’s MN61.

In the words of Hainbach: “Nothing really sounds like [a] wire recorder… a haunting quality, sort of like the ghosts of the past caught in a metal cage”.

Try Wires today. You don’t have anything like it.

Available in VST2, VST3, AU, and AAX (64-bit) formats.